Charles Bonnet Syndrome in Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Comprehensive

Abstract

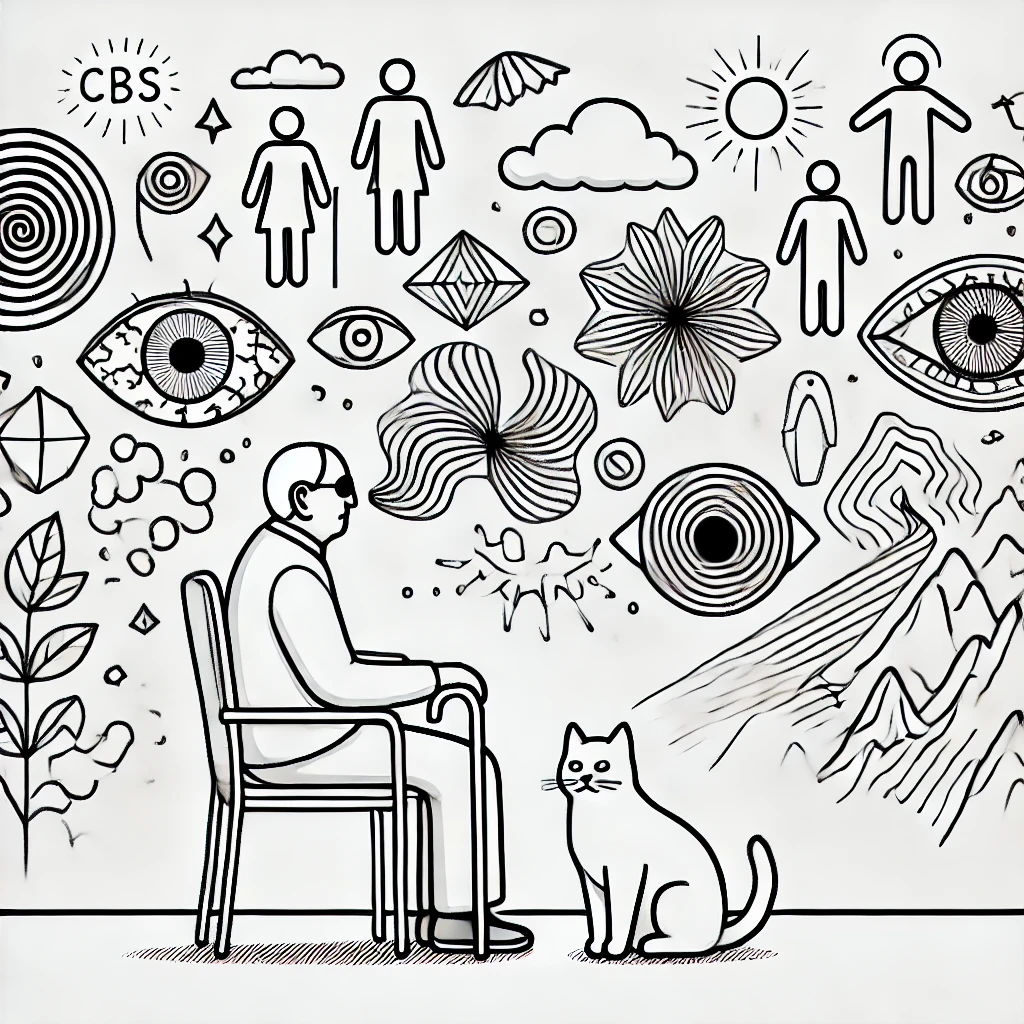

Charles Bonnet Syndrome (CBS) is a condition characterized by the presence of complex visual hallucinations in individuals with visual impairment, particularly in the elderly population. It is commonly associated with age-related macular degeneration (AMD) [1,2], glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy. This review synthesizes current research on CBS, with a primary focus on its prevalence in AMD patients, including its clinical presentation, pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, and management strategies. We explore emerging therapeutic approaches and the potential role of artificial intelligence (AI) in screening and managing CBS. The review also highlights the psychological impact of CBS and the importance of awareness among healthcare professionals. Future research directions are discussed to enhance understanding and improve patient outcomes.

1. Introduction

Charles Bonnet Syndrome (CBS) is a fascinating but often underdiagnosed condition in which visually impaired individuals experience complex, vivid visual hallucinations [3]. The prevalence of CBS varies significantly, with studies estimating rates between 10% and 40% among those with significant vision loss, and it is notably high among patients with AMD [4]. While CBS was first described in 1760 by Charles Bonnet, its mechanisms remain partially understood. Most affected individuals maintain intact cognitive function, distinguishing CBS from neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia or Parkinson’s disease [5].

CBS is strongly associated with AMD, the leading cause of vision loss in older adults, making it a critical consideration in ophthalmology [6]. As vision loss due to AMD progresses, patients are at an increased risk of developing visual hallucinations characteristic of CBS [7]. Given the rising global prevalence of AMD, the incidence of CBS is expected to increase significantly, necessitating improved diagnostic awareness and management strategies [8].

2. Clinical Features and Diagnosis

2.1 Symptoms and Hallucinatory Patterns

CBS hallucinations are typically repetitive, stereotyped, and non-threatening, differing from hallucinations associated with psychiatric illnesses [9]. Common features include:

-

People, animals, or geometric patterns

-

Hallucinations lasting from seconds to hours

-

No associated auditory or sensory involvement

-

Preserved insight, meaning patients are aware that the images are not real

Patients with AMD often report that CBS hallucinations correlate with periods of sudden visual deterioration, suggesting that rapid vision loss may trigger compensatory activity in the visual cortex [10]. Additionally, studies show that CBS prevalence in AMD patients increases significantly as central vision loss progresses [11].

A recent case report of CBS following optic neuritis suggests that visual deafferentation alone can trigger hallucinations, reinforcing the role of sensory deprivation in CBS pathophysiology [12].

2.2 Differential Diagnosis

Accurately diagnosing CBS is essential to distinguish it from conditions such as Lewy body dementia, schizophrenia, and delirium [13]. Key differentiating factors include:

-

CBS patients have no cognitive decline

-

No emotional distress linked to hallucinations

-

Absence of other sensory hallucinations

Despite these clear differentiators, CBS often goes undiagnosed because patients may hesitate to report their hallucinations due to fear of being labeled as having a psychiatric disorder [14].

2.3 Neuroimaging Findings

Recent functional MRI (fMRI) and PET scan studies suggest that CBS is related to hyperexcitability of the visual cortex due to visual deafferentation [15]. These studies demonstrate increased activity in the ventral occipital cortex, suggesting that the brain compensates for lost visual input by generating spontaneous visual imagery, particularly in AMD patients with severe visual loss [16]. Additionally, AI-driven neuroimaging techniques are beginning to play a role in identifying biomarkers of CBS in AMD [17].

A computational model proposed for CBS suggests that the syndrome arises from the brain’s generative processes compensating for sensory loss, further reinforcing theories that CBS is a natural reaction to decreased sensory input rather than a pathological disorder [18].

3. Pathophysiology

3.1 Cortical Hyperexcitability in AMD Patients

-

Loss of afferent input from the retina due to AMD leads to increased spontaneous neural activity in the visual cortex, resulting in hallucinations [19].

3.2 Release Phenomenon Theory

-

The brain "fills in" missing visual information, much like phantom limb sensations after amputation. This process is exacerbated in AMD due to the progressive nature of central vision loss [20].

3.3 Neurotransmitter Dysfunction Hypothesis

-

Abnormalities in dopaminergic and serotonergic systems may contribute to CBS, similar to other hallucination-related disorders. AMD-related visual deprivation may enhance susceptibility to neurotransmitter imbalances [21].

4. Management and Treatment Approaches

4.1 Non-Pharmacological Approaches

-

Patient Education: Reassurance that CBS is benign significantly reduces distress, particularly in AMD patients who fear worsening cognitive decline [22].

-

Sensory Stimulation: Increasing visual input (e.g., blinking, moving eyes) may interrupt hallucinations.

-

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Helps patients develop coping strategies for hallucinations.

4.2 Pharmacological Interventions

-

Antipsychotics – Used cautiously, as CBS is not a psychiatric disorder.

-

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) – May be beneficial in some cases.

-

Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors – Used in cases with cognitive impairment but not first-line treatment.

4.3 Emerging AI-Based Screening and Treatment

Recent advances in AI-driven telemedicine solutions allow remote monitoring of visual function and could be used to detect early CBS symptoms in AMD patients [23]. AI-powered home-based retinal imaging tools may help track disease progression in AMD patients and correlate with CBS development [24]. Moreover, AI is being developed to analyze neuroimaging data, helping identify early CBS biomarkers and differentiate it from other neuro-ophthalmic disorders [25].

5. Future Directions and Research Gaps

- Better Epidemiological Studies: More precise prevalence estimates in AMD patients are needed.

- Neuroimaging Biomarkers: Identifying reliable fMRI patterns linked to CBS and developing AI-assisted detection models.

- AI-Based Interventions: Use of AI for early CBS detection and personalized treatment approaches.

- Integration with Low Vision Rehabilitation: Multi-disciplinary approaches to improve CBS management in AMD patients.

6. Conclusion

CBS is a common but underrecognized phenomenon in visually impaired individuals, particularly in those with AMD. With the increasing prevalence of AMD, ophthalmologists and neurologists must improve diagnostic accuracy and patient education. Advancements in AI-assisted screening and telemedicine hold promise for better CBS management. Future research should focus on biomarkers, treatment optimization, and interdisciplinary care models to enhance the quality of life for AMD patients experiencing CBS [26].

By continuing to refine diagnostic tools and integrate AI into ophthalmic care, we can better support AMD patients experiencing CBS, ensuring early intervention and improved quality of life.

References

-

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10792-024-03298-0

-

https://www.rnib.org.uk/your-eyes/eye-conditions-az/charles-bonnet-syndrome/

-

https://academic.oup.com/brain/article/144/1/340/6053150?login=false

-

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/25158414241232285

-

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/25158414241294022

-

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/25158414241275444

-

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/25158414241294177

-

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/25158414241305500

-

https://www.canadianjournalofophthalmology.ca/article/S0008-4182(24)00010-3/fulltext

-

https://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003134

-

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1755-3768.2010.02051.x

-

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/25158414241280201

-

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/25158414241294177

-

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/25158414241275444

-

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/25158414241305500

-

https://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003134

-

https://www.canadianjournalofophthalmology.ca/article/S0008-4182(24)00010-3/fulltext

What is Charles Bonnet Syndrome (CBS) in AMD patients?

Can age-related macular degeneration cause hallucinations?

Why do AMD patients experience visual hallucinations?

How is Charles Bonnet Syndrome diagnosed in people with AMD?

Is there a connection between CBS and vision loss?

What are the most common symptoms of Charles Bonnet Syndrome?

Can artificial intelligence help diagnose Charles Bonnet Syndrome?

What treatments are available for CBS in AMD patients?

How common is Charles Bonnet Syndrome in people with macular degeneration?

What causes visual hallucinations in visually impaired individuals?

Are CBS hallucinations a sign of dementia or mental illness?

How do AI and telemedicine help in managing CBS?

What are the latest research findings on Charles Bonnet Syndrome?

Can CBS be prevented in AMD patients?

How can ophthalmologists detect Charles Bonnet Syndrome early?

What role does the brain play in CBS hallucinations?

Is CBS related to Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease?

Why do some people with AMD experience phantom images?

What medications help reduce CBS hallucinations?

How do CBS symptoms differ from psychiatric hallucinations?

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.